The Writing of Logan Taylor Brown

On Love

“We’re neither pure, nor wise, nor good; we do the best we know.”— Voltaire

The most vile, the simplest, and the catatonic are among those who have been clutched, at one point or another, by the soft hands of love. This is so -- no human who has passed through a lifetime can escape an encounter with the immeasurable dance that is love. One cannot move through life without being grazed by it, no matter how strange, brief, or distant. If the span of life were but a single moment, then mixed within the chorion and villi of the placenta would be the first act of Love: the consumption of nourishment. We are not to escape the radiance of this ethereal concept, for if we could, the paradox that is a human being would cease to exist. Even if one tried to run from love, they would only trip over the contradiction of their own existence — a beast caught between love and the loss of it, between what we crave and what we are afraid to hold.

The dual nature of being human is not born of good or bad, I believe, but from the ideal of love and its absence. The gambler who loses everything, the alcoholic who laments only pain and sorrow, the spurned man-child who deals in cowardice — all can recall the fabric of care once draped upon them. The widow, the mute, and the blind, if asked, can each procure an example. Even those imprisoned for wicked actions, though they have contorted and manipulated the concept of love, are not exempt from the experience of a time remedied by a guest of higher calling.

Love is not what the human makes it out to be. There is the idea of it — this we can try on in our minds and hearts. But like water, love is neither ours to define nor to design; rather, it designs us. It grows legs to run with. It hides in the charcoal of an artist’s instrument, in the trembling note of a song that pulls one apart. It is the cliff one overlooks, and it is the trust that lends itself to the fallen’s landing. Heartbreak is as painful as it is because love is abandoned. Sometimes, it seems a great distance must be traveled with love left behind. Sometimes, the work is to understand that all of it is internal — that love is the bridge permitting mirrors to face each other. And yet, profundity is never beyond the grasp of intention. What will free one, suspend one, bind one, and transfix one will remain hidden in plain sight.

Love and perception are the best of friends. It is learning to see that is hard. A slew of other pillars are uncovered in the process of bringing order to one’s experience: respect, dignity, and integrity come out to play. In the field of one’s mind, the frolicking of being human blends a little of each, creating the whispering notion that life is worth living — worth uncovering, exploring, deciding, and letting go. There is love within commitment and spontaneity, within the mundane and even the profane.

“La raison d’aimer, c’est l’amour.”

Guy Bourdin’s “Red Dress”

On Fear

“A man who fears suffering is already suffering from what he fears.”

— Montaigne

They tell you as a child: face your fear. Head-on. No shield, no armor. Bare as you can be — the only weapon you carry is yourself. Fear can be starved, but it can't be ignored.

When you come down from the tornado winds of panic — ripped up, scattered, in pieces — you'd do well to realize there was never anything to fear. Fear is yours to command. It's when one forgets this that the beast of cemented ideology seems to loom, casting a shadow one foolishly believes spans unseeable distances.

But you persevere. You make up reasons to lean into other feelings — pull from joy, anger, hope, and understanding. And when you're naked, raw, alone, you call out to trust, to choice, to belief that won't deplete. With some rope — imagined or real — you tie those anchors to your soul and keep moving. One foot, then the other. You follow what every human carries, somewhere deep inside: intuition.

And when you eventually reach the end of the shadow, in that pixellated space where light and darkness meet, don't be surprised if a great portion of you bemoans perplexed emotion over leaving the shade. What was scary has become familiar, and your bare self rings the last bells of trepidation over the idea of leaving a makeshift shelter in fear.

Until you step into the day that rains light over you — you whose strength was but a pinpoint, you who grew strong in all you overcame, perhaps at first, when the dazzling calm of a storm passing runs the length of you, you shudder in its warmth. In time, now clothed and shielded in safety, in the quiet calm, you realize: fear doesn't vanish. It slips into the back of your mind like a worry stone in your pocket, a thing you can rub without even thinking. And somewhere, deep inside, you cradle the version of yourself that used to be ruled by fear.

You carry that part with you — not as a weight, but as a reminder. Because without it, you would never have tasted what it means to live without obstacles. You'd never know the freedom of the fields you now run through with wild abandon.

“Fear is only as deep as the mind allows.”

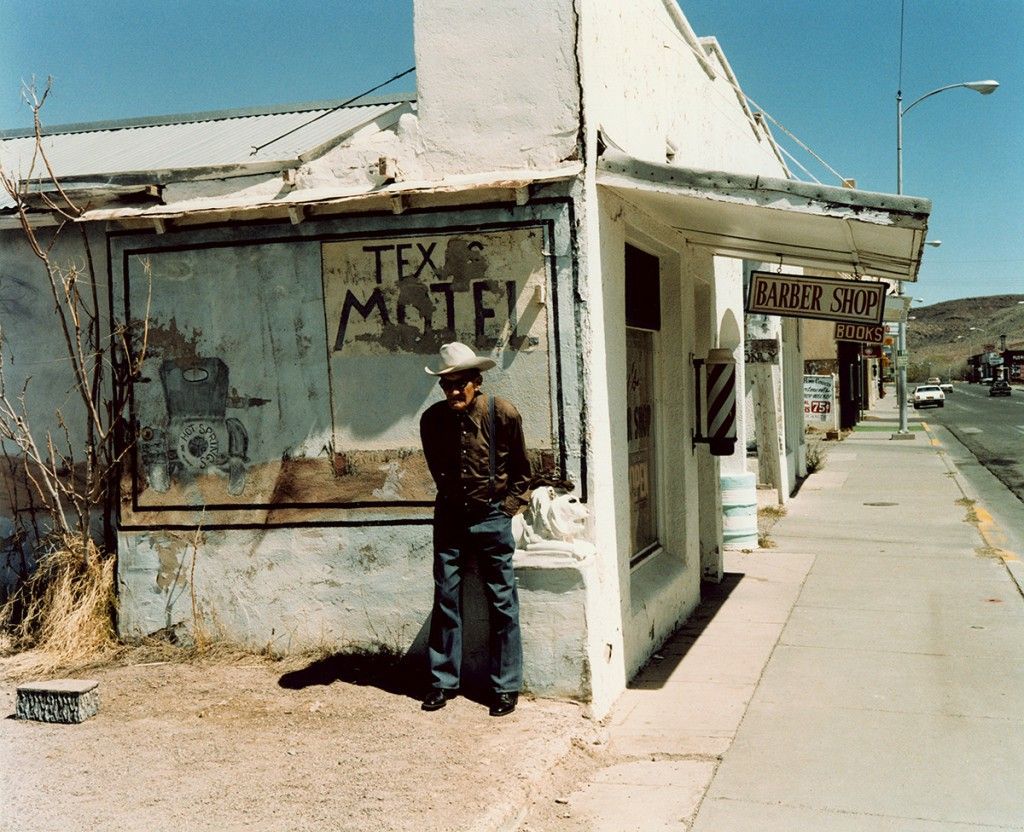

Wim Wenders’ “Written in the West”

Excerpt from the short story “Royce and Mara”

Royce’s Daddy

Royce and his predecessors had long since lost the Americans’ interest in farmed land and produce. In time, they stopped the payments on the newest version of the mortgage. The great American dream — to be in debt — had sought, found, and conquered Royce and the family who’d raised him.

See, Royce’s daddy didn’t take life lying down. Only death, an eternal sleep, suited his fancy. When the first talks came about losing the acres to the sparkling new government building — the one that sat up on Brown Street like a proud kid with a loud, swollen insolence — well, John Fisher wouldn’t hear a thing of it. Proud and towering, as though the milk in his bones worked overtime, he fought those conversations. Then he fought the notion it was really going to happen.

Then he fought the notarizer, the signature, the final submission to reality came, thick and ugly.

And when he came home that night, after the deeds were transferred and succumbed to bureaucratic filing, John Fisher had not an ounce of fight left in him. He ate the dinner Mrs. Fisher cooked up, swathed the hair of his four children, and tucked them into bed. Sandy — Mrs. Fisher — knew something other than the usual bad was working in him, but her mind told her it wasn’t her place to ask. A man did what a man pleased, and if he wanted to show emotion or say a soft I-love-you to the children on a hard day, who was she to interfere.

Later that night, when John slipped out of the warm bed — careful as he quietly unfastened himself from the quilt’s embrace — and when he slipped down the attic steps, out the back door, and into the adjacent barn, nobody in the house knew a thing. They kept on sleeping. The two boys in their shared bed, the two girls in theirs, Sandy rolling over, dreaming of a hot day where she’d be bound to stay perched on the veranda. All peaceful tidings in a house that had just lost all right to peace.

It was John Fisher — Royce’s daddy, proud and towering — who sacrificed his pride, shrank from his height, and slipped a roughly thrown-together noose over his stern neck — the great American dream.

Royce found him dangling in the early hours of the morning.

The cows looked up with tired eyes when the boy screamed.

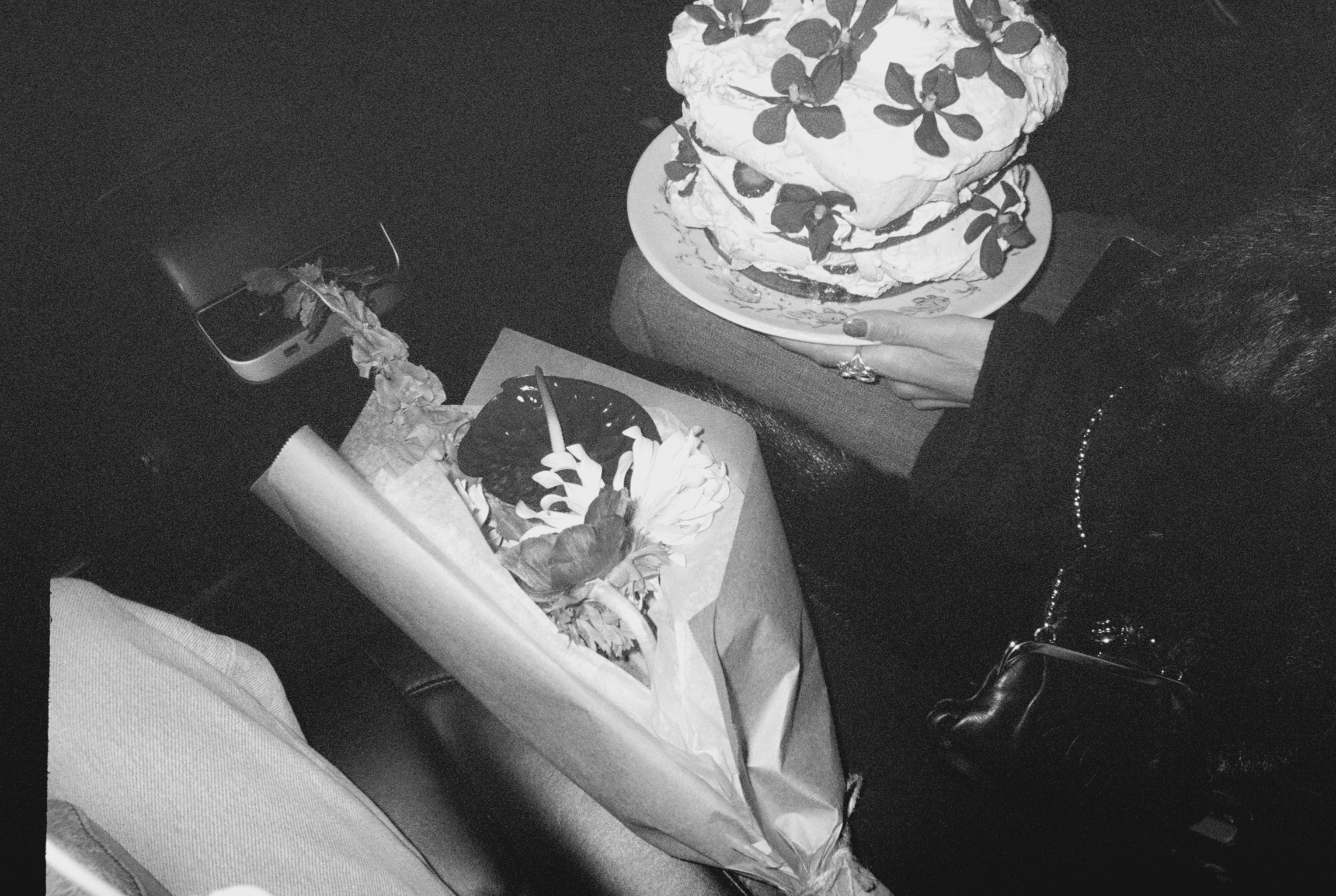

Logan Taylor Brown’s “Iza’s Offerings”

Excerpt from the novella “Anywhere I”

Railroad Apartment

“So, this is where your room is.” I went to open the door of the room right off the landing.

“No, no. I mean—you can open it,” she said. I did. “But that’s just a spare room we don’t really have any use for right now.” She walked away from the stairs and me. I followed her, not realizing she meant my room was down here in the basement, a few paces from the staircase. “This is your bathroom,” the light switch flipped up to reveal a yellow-tinted half bath. And then, “sorry for the mess, I’ve been meaning to get down here.” She moved apple crates filled with art supplies and loose clothing out of our way, opening the final door.

The room was of decent size, a rather big square. In the far-right corner were box springs, void of a mattress. The ceilings were low.

“Must be the luggage portion of the railroad apartment,” I said.

Adair let out a solo “ha” in response. On the wall hung a skinny mirror.

“I had to throw out the mattress—bed bugs nearly munched it away.” I came to find out Adair would say shocking things in extremely jovial tones. “But that was months ago. An exterminator’s been here and all that.”

“Aw, cheese, I heard about those. Damn, bugs scare the shit out of me.”

“Don’t even worry about it, you’re all good, I promise. I have a few quilts, and you could use one of my pillows, or we can take some from the couch upstairs in the meantime?” She went back into the hall, returning with her arms filled with two hefty quilts and dumping them on the bed. “I’ll see what I can do about getting a mattress down here.” She seemed genuinely embarrassed for not having thought of it before I arrived.

I’d never slept on box springs, I remained unconcerned. A girl with somewhat regular standards probably would have had some qualms with ending her day on rusted metal—thankfully for Adair, she wasn’t around.

“I’ve got a knack for passing out anywhere. I’ll be fine.”

She looked at me sideways and shrugged. “I’ll still keep an eye out.” Checking the watch on her left wrist, she said, “shit, I’ve gotta get going. Um, is there anything else?” After giving me a few food and bar recommendations in the neighborhood, she handed me a set of keys. “Lorenzo should be home soon-ish. If you need anything, you have my number, or you can ask him—he won’t bite.”

With that, she was off. I heard the front door slam shut as I role-played a mother bird, setting up my nest.

My luggage was a set of vintage cream-colored vinyl suitcases. I clicked the locks together, and the box sprang open. There was no table or desk to put anything on, so I placed things against the wall next to the springs. An incense holder with its accompanying frankincense. After two minutes of that burning, I realized there was no ventilation in my underground bunker. The smoke danced above my head.

Next to come out of the suitcase were my couple of books that went with me everywhere—Another Country, by Baldwin; East of Eden, by Steinbeck. Neither of them rare finds, but my loyal travel companions. A picture of my mother and me, a CD player and headphones, and this small silver trinket of two women embraced in a frozen waltz. The room was all put together.

When the lights were out, the basement ceased to be a room and became a condition, one I would learn to inhabit.

© 2025 Logan Brown. All rights reserved.